Treatment goals

Healing and defect healing

Before starting therapy, you should always be clear about the treatment goals. The real goal of therapy is of course always healing. Often, however, a real cure cannot be achieved at all, e.g. in the case of chronic diseases such as asthma or rheumatism or also with certain cancers.

Then, of course, the treatment goal must also be formulated accordingly. For example, pneumonia caused by bacteria can usually be completely cured with appropriate antibiotic therapy, i.e. the lungs do not suffer permanent damage and are fully functional again after healing. It looks different in the case of a heart attack, for example.

A part of the heart muscle is irreparably damaged by the vascular occlusion, i.e. the heart muscle region originally supplied by this blood vessel dies due to the lack of blood supply. If treatment is started in good time, even extensive heart attacks can be survived today because the functionality of the heart muscle can at least partially be maintained by the cells not affected by the infarction (if a cylinder in a car engine is defective, the car can still drive, but no longer with it full engine power). However, a complete cure is not possible because dead heart muscle cells no longer renew themselves. In this case, we are talking about defect healing with a correspondingly reduced performance.

There is no cure for osteoporosis

In principle, unfortunately, it is still the case that osteoporosis has not yet been cured, at least not in the sense of a complete “restoration” of the originally healthy situation. Above all, it has not yet been possible to completely rebuild the bone substance that was once lost and to restore the original bone condition as it existed when the peak bone mass was reached around the age of 20-25. With the drugs currently available, at most a very limited increase in bone mass can be achieved, which seldom exceeds 10% of the bone mass still present at the start of therapy within a few years.

But even this relatively small increase in bone mass can bring about a significant improvement in the clinical picture. It is also not (or only to a very limited extent) possible to “repair” or straighten a collapsed vertebral body. The changes (decrease in altitude, wedge vortex formation, fish vortex formation, etc.) usually persist, although at least bony stabilization (consolidation) can of course also be observed after a vertebral collapse. However, this cannot be compared with healing, e.g., a forearm fracture (radius fracture) using plaster of paris treatment. A certain improvement or “re-erection” of a collapsed vertebral body can be achieved today with the so-called balloon kyphoplasty.

Important: definition of the treatment goals

It is therefore very important to set a treatment goal before making any therapy decision. On the one hand you protect yourself against false hopes about the changes to be achieved, on the other hand against disappointment if unrealistic expectations do not come true! In the same way as the therapy planning and the exact selection of any medication that may be necessary, the most precise diagnosis and classification of the type of osteoporosis present is also necessary in order to determine the treatment goals. For example, in the case of cortisone-related (secondary) osteoporosis in a highly active rheumatic disease, it would be desirable if cortisone could be discontinued as the triggering cause of osteoporosis. However, if the patient cannot live without cortisone, discontinuation of the cortisone cannot, of course, be a treatment goal. In this case, there is nothing left but to treat the osteoporosis symptomatically.

Lowering the risk of bone fractures

The most serious consequence of osteoporosis is the osteoporotic bone fracture and especially the vertebral fracture and the femoral neck fracture. The most important goal of treatment should therefore always be to prevent bone fractures as much as possible. We now have a whole range of highly effective drugs for which a relevant effect has been clearly proven in large, international studies. This means that the risk of bone fractures can be greatly reduced with these drugs. This reduction in the risk of fracture (fracture risk reduction) is particularly true for osteoporotic vertebral fractures, and to a limited extent also for the femoral neck fracture and for all other (peripheral) bone fractures. I consciously say “osteoporotic vertebral fracture” because only this occurs spontaneously, i.e. without any external influence.

For example, if someone falls off a ladder while cleaning windows or suffers a car accident, even the best medication will hardly save them from a broken bone – regardless of whether they have osteoporosis or not! The typical osteoporotic bone fracture is defined as a fracture after an inappropriate accident event (low trauma fracture), which usually does not lead to a fracture in healthy people. In the case of a vertebral fracture, this is pretty clear, at least as long as no accident event is known. With all other bone fractures and even with the femoral neck fracture – which is often regarded as the osteoporotic bone fracture par excellence – this is not a matter of course, as these do not occur spontaneously.

Lowering the risk of falling

The reduction of the risk of bone fractures by means of medication works on the one hand through a direct influence on the bones or on the bone metabolism and on the other hand through a reduction in the frequency of falls, the latter mainly through calcium and vitamin D. This means that we have the second treatment goal, namely a reduction in the Frequency of falls. Fewer falls mean fewer broken bones, of course, this is especially true for the so-called “peripheral” bones (forearm, upper arm, thigh neck, lower leg, etc.), but less so for the (central) osteoporotic vertebral fracture, which is usually not one traumatic (accident) fracture. For the simple basic therapy with calcium (1000-1200 mg calcium and 800-1000 iE vitamin D daily), an impressive study on several thousand residents of old people’s homes (Chapuy, Meunier) showed a significant reduction in the frequency of femoral neck fractures by almost 50% compared to a placebo (ineffective, but identical-looking tablet) detected. In other studies (Minne, Bad Pyrmont, Bischoff, Switzerland) with the same dose of calcium / vitamin D, a significant reduction in the frequency of falls by approx. 50% compared to a control group only treated with calcium was demonstrated.

In this respect, it can be concluded that the reduction in the number of femoral neck fractures under combination therapy with calcium and vitamin D (Chapuy, Meunier) is less due to the direct influence of calcium / vitamin D on the bones, but mainly due to the reduction in the frequency of falls Vitamin D is conditional. 50% fewer falls and 50% fewer femoral neck fractures – that sounds convincing, although a direct connection between the results of these two studies has not yet been proven. The results of several other studies point in the same direction, in which a positive effect of vitamin D and the active vitamin D metabolite (D hormone), which is actually effective and arises from normal vitamin D (through conversion in the kidneys) By-product, on the muscle strength and on the neuromuscular coordination (transmission of nerve impulses to the muscle) was determined. This also supports the study results regarding the effect of calcium and especially vitamin D on the risk of falls. Therefore calcium and vitamin D have become indispensable in the treatment of osteoporosis (especially in older patients) – contrary to some publications in the press, the combination of calcium and vitamin D alone is not effective for the treatment of osteoporosis!

Activation of the bone structure

A logical treatment goal would of course be to replace the broken bone with new bone and to do this as easily as possible, e.g. with a drug. Unfortunately, the potency of the currently available drugs to activate the bone structure (reconstruction) is very limited, although new and very effective drugs (parathyroid hormone) can be expected in the very near future. The fluorides, which were very common in the treatment of osteoporosis until a few years ago, were regarded as drugs that were supposed to stimulate bone formation, but there are now justified doubts about the effectiveness of the fluorides. After longer-term and higher-dose fluoride treatment, an increase in the risk of bone fractures was even observed in some studies.

To date, only a bone density measurement can provide evidence of whether bone build-up has actually occurred during therapy, and even here an increase in bone density is not always equated with real bone build-up, since – depending on the method used – there are possible sources of error (microcallus formation, wear and tear the spine or spondylphyte formations on the vertebral bodies, which often lead to incorrectly high results, especially when measuring with the DXA method).

Lowering the rate of bone loss

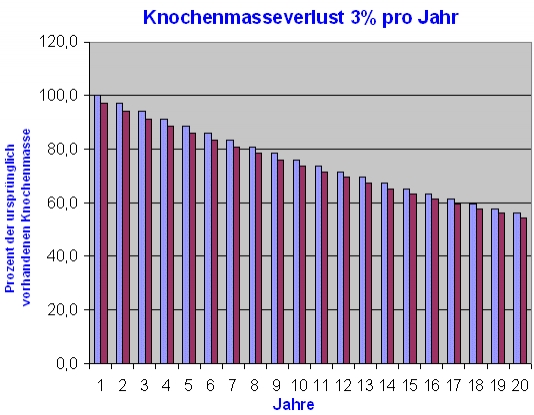

An increased rate of bone degradation leads to an increasing deterioration in bone quality – both due to the further reduction in the existing bone mass and, in particular, due to the progressive destruction of the bone structure. If the loss of bone mass is higher than 3% per year, we speak of a so-called fast-loser situation. Around 30 – 40% of all women after the menopause show a statistically higher rate of bone loss in the sense of an almost-loser situation. 3% bone loss per year quickly adds up to pronounced loss of bone mass. In the following figure, a constant bone loss rate of 3% per year – corresponding to a nearly loser situation – was assumed over a period of 20 years. Starting with 100% bone mass at the age of 50, for example, by the age of 70 almost 50% of the total bone mass still present at 50 years of age would be lost!

The bone density at the age of 70 would actually only be 54.4% of the bone mass originally present at the age of 50, although it is by no means certain that the original peak bone mass (which is reached between around 20 and 25 years of age) at 50 years of age ) is still completely present or significant bone loss has not occurred by the age of 50.

Pain management

Pain management

The treatment of osteoporosis-related pain (mostly back pain) is of course also an important treatment goal, although this has nothing to do with the causal (causal) osteoporosis treatment. Osteoporosis mainly leads to acute (after a fresh vertebral fracture) and chronic (if there is one or more vertebral fractures) back pain, but not every back pain is caused by osteoporosis. In particular, an increased rate of bone breakdown does not normally cause back pain, just as a hole in the petrol tank of your car does not lead to any restrictions in driving characteristics (of course only until the tank is empty and the car stops or a vertebral fracture occurs in the case of osteoporosis). Chronic osteoporotic back pain is primarily a muscle pain (caused by tension and hardening of the back muscles due to the static changes in the spine after vertebral fractures).

The acute pain after a fresh vertebral fracture usually subsides once the fracture has consolidated (defect healing), although the vertebral body is of course lost in height after the vertebral fracture. Since this pain can become chronic (i.e. the pain becomes a normal state if left untreated), one should not be afraid to seek appropriate pain medication for this pain. If the chronic back pain cannot be controlled with conventional pain medication (aspirin, ibuprofen, Novalgin, Voltaren, diclofenac, etc.), which unfortunately often lead to stomach complaints or damage to the kidney function (especially with prolonged use), one should rely on so-called Use opiates (morphine derivatives). These are now available e.g. in the form of very effective pain plasters that attack the central nervous system (which seem to have fewer side effects than the usual administration via syringes or infusions). In the case of chronic and persistent pain, you should definitely consult a specialized pain therapist.

Improving mobility (Verbesserung der Mobilität)

Another important treatment goal is regaining or improving mobility (mobility, ability to do normal everyday activities again). In addition to pain treatment, this is primarily a domain of physical medicine such as physiotherapy, movement therapy, osteoporosis gymnastics or other physical applications such as mud , Bar baths, stimulation current, electromagnetic fields, etc. Here, too, you should turn to specially trained therapists, although today the question of how the statutory health insurance companies will assume the costs or the often inadequate supply of such facilities at home (especially if you are not in a big city lives) can be limiting.